The following memoir is transcribed by Jean Carpenter from a copy of the Sunday Tribune-Eagle (Cheyenne, Wyoming) of July 20, 1980, and is reproduced here with the permission of Cheyenne Newspapers, Inc. (Copyright 1980. All rights reserved.)

Carl Sackett Knew What the West Was Really Like

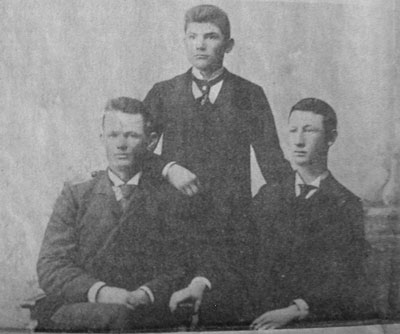

"Editor's Note: Stagecoach robberies, the James Brothers, Buffalo Bill, Indian maneuvers—they were all a part of the life of Carl L. Sackett, Sr. Sackett, born in 1876, died at the age of 96. He was the oldest practicing attorney in Wyoming.

Following are excerpts from a transcript of a tape-recorded interview of Sackett in Los Angeles in 1970. The interview was conducted for FM station KPFK by William Malloch."

"I'm one of the last frontiersmen remaining who lived through the period of the migratory buffalo to the jet age in the Far West. I was born before the Battle of the Little Big Horn where Custer and his men were killed.

In September of 1880, with two ten-mule teams hauling two big freight wagons, we moved north from Cheyenne about 360 miles to the area occupied by General Cook at the time of the Custer Battle. I passed through no towns or fences going the 360 miles.

My father was occupying part of the buffalo range when the Deadwood Stage was carrying a gold chest from Deadwood to Cheyenne. Robbers took the gold chest. Superintendent Vorhees talked with the stage driver to get the description. You might think they talked about people. He didn't talk about people. He talked about horses. The robbers rode horses, and frontier people and the Indians knew horses at that time when they wouldn't know a woman. They followed the horses by inquiring of frontier people and the Indians about horses that went by, and they finally located them in western Nebraska. They planned on how to get close to the underground cabin where the robbers had "holed up." Then some people came out of the dugout, one carrying the gold chest. The superintendent thought he knew him as a robber. His gun cracked and down he went. Each man came out shooting. Every man who came out went down before he could get on his horse. They never robbed another stage.

We moved in the fall of 1880 up to Goose Creek—Little Goose Canyon. My father homesteaded a hill on what was later named Hanna Creek. There was a trapper's cabin—one room, dirt floor, dirt roof, with a fireplace laid up with mud in the corner. We cooked on the fireplace and ate there. My father purchased squatter rights and homesteaded on 160 acres. When the Indians went to the battle with General Custer they kept retreating until they got into Canada. Then they came back when arrangements were made to surrender to General Sheridan. The Indians camped on my father's homestead. I saw them when they arranged their tee-pees and how they rode their horses. They still were "fighting Indians," and the horses had eagle feathers in their tails. My brother and I walked up to a head of a hill at the edge of Sackett Creek where we could look down on their camp and see them do all their maneuvers just by signals—no words. The maneuvering was marvelous.

People got along on meat—chiefly buffalo, deer and antelope. Of course, wild birds came in and landed on the streams, so they had ducks and geese, but no eggs. They had taken a few chickens, but chickens had to be developed. I lived on buffalo meat, fresh and frozen and dried, until I was ten years old, as my chief meat diet. They did manage now and then to get some corn and corn meal and flour. People ate liver and marrow gut. Sometimes people—believe it or not—took the food from a ruminant (that's from a deer or antelope or buffalo, partly digested grass from the stomachs of the animals). That way they got all the elements of vitamins that you could get from green stuff anywhere. And the frontier people always knew what kinds of wild plants were edible. They ate them, sometimes raw, but usually cooked.

Now, in the books you find nobody who really counted the buffalo on the buffalo trail. But my father and Buckskin (a hunting partner) were surrounded by buffalo in the springtime—so many they couldn't count them. They figured out how to cross-section the area and count the number of buffalo in one square. They made an estimation, which they said was quite accurate, of 40,000 in sight from one point.

Now, other matters you may be interested in—for instance, in Cheyenne I met Calamity Jane. Some reports are out that discredit her as a woman. But Warren Richardson, who knew her those years, said nobody should speak ill of that woman. She devoted herself to helping people. If they were sick or injured she usually was there rendering assistance. She did go swimming with the soldiers. But she was a very competent and capable pioneer woman. I never saw an unfriendly act with her when I was in Cheyenne.

The streets were all dusty and there was no bathing. There was no sewer system and no water system when I was there in those two years, 1879–1880, and no electric lights. On Sackett Creek my father was appointed the first Wells-Fargo agent in the area. My mother would serve tables and feed the passengers on the stages. Among the people who came in to eat one day were Frank and Jesse James of the James Brothers Gang. They ate at the same table with me. I had a cigar box for people who felt like giving money to kids. And they put money, quarters or half dollars, in this cigar box for me. I noticed my father had these bullets in his pocket and was standing right close to this shotgun. Evidently the James Brothers figured that before he was killed that one of them would be dead, so they ate and they showed no signs of being dangerous while I was there. On Little Goose Creek there was an old colored man who had a house at one end of which had a blacksmith shop. He was a friend of the James Brothers in Missouri who was brought out to shoe and care for horses by the Bozeman trail. He evidently reported to the James Brothers when the stage went by whether there was some indication that it carried gold.

(Sackett was asked his impressions of Colonel Cody.)

He was a very outstanding human—his attitude and atmosphere. He was kindly with people who were friendly, but there was no question that he was one of the most serious generals in the war with Indiana, when Indians were warlike. He was tall, about six feet, and he was not fat. He was athletic in appearance and quiet in his maneuvers and motions. He sometimes wore his hair long, in curls. But later he cut his hair just like every man had. But he wore his hair long to impress the Indians. Some people try to curl their hair in order to look like a frontiersman. That isn't common with frontiersmen. It's only with people who want to make a show. But Custer made a great impression with the Indians with his hair, and other people did too. So Buffalo Bill sometimes wore his hair long, but I don't think he did that for white folks.

(Sackett was asked to compare frontier to modern life.)

In Washington or New York or Chicago you are in more danger than you were from the Indians on the plains—because you can't tell who is going to throw a chain around your neck or grab your arm or shoot you or knife you. I grew up breaking horses. A kid then wanted a horse just like a kid wants an automobile. Horse was king. Every man who was of any account had his own horse. "Horses" was wealth, not only with Indians but with white folks. If you had a horse you could use it. You could do something. The frontier was won with a man with a gun and an ax on a horse. He could use his ax to build most anything, carve on wood, make bridges, boats, rafts; and he could use a gun to feed himself."